A View from the edge of the Heath

I woke thinking I should take myself out for, effectively, an 'Artist Date'. My first idea, the V&A East Store House, seemed too depressing. All those important cultural artefacts packed into an industrial warehouse, on shelves of steel and unfinished MDF, miles from any ties to their creators.

No - something closer to home would be better.

Besides Keats' House, I've never explored much of the borough I live in despite it having housed some of my favourite figures of history. And my favourite book! In 'A Diary of A Nobody', Charles Pooter goes for "a good long walk over Hampstead and Finchley" to 'The Cow and Hedge' which still exists today but now as 'The Old Bull and Bush', which I find quite funny.

Something closer to home. I landed on the Freud Museum.

Just off of Finchley Road, in a line of red brick houses and well kept front gardens, highlighted by two large blue plaques, is the final home of Sigmund Freud and his daughter Anna Freud. I'd applied to work here when I first left university because of my new found love for Lacanian Psychoanalysis. I felt as though I had discovered the solution to what I had always hated about traditional therapy (often times CBT). After every single session I feel freer and at the same time more secure. Freud compares it to archeology, layer-by-layer uncovering "the most profound and valuable treasures" in a person.

It is in this house that the father of Psychoanalysis passed away. And so, though it was a surprise to me in the moment, maybe it is expected that as I first entered I felt myself tear up. I don't think I was alone in this as a woman darted past me, into the toilets, wiping her eyes. She had been looking at an exhibit titled 'Sigmund Freud Arrives in London as Refugee'.

Freud's study was nicely preserved, but I was sad to see that Anna Freud's room had its furniture pushed up against the windows to allow for a walk way. There also stood huge glass cabinet housing some of her knitting and weaving work, while the loom she used was awkwardly sat in the corner, its threads slack and knotted.

The room of Dorothy Burlingham, described as Anna's "lifelong friend" or "colleague" in the museum's labels, was entirely shut off as well as Anna's study and the room Sigmund Freud had died in. I assumed these were choices made by Anna when she died; she had written instructions for the conversion of the house into a museum about her father, not herself.

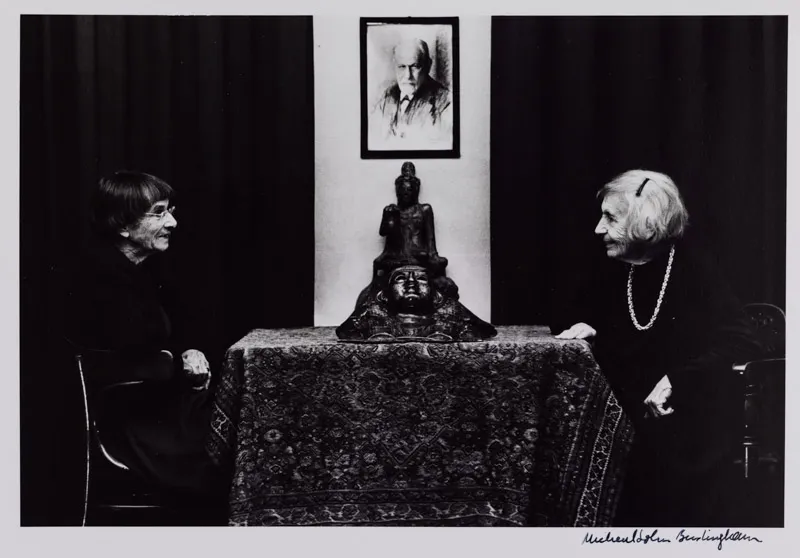

As I left, I gave a final look to a set of chairs in Freud's study at which Anna and Dorothy had been pictured sitting, looking at one another.

I walked further into Hampstead, bought a sandwich and a coffee in town, passed the station, several artisanal butchers, a Gails, some fashion brands I would later look up on Vinted, and then stopped at a sign for 'Pilgrim's Lane'. Some vague memory told me this road led to a familiar part of the Heath, so I followed it and was proven right. As my calves began to ache from an embarrassingly gentle incline, I reached a bench on top of a mound and sat on the edge of the Heath to write what you have now read.

In Keats' House, there is a window framing the view of an old tree on which - a museum label explains- it is likely a Nightingale sang out to inspire Keats' famous Ode. Across the hall, in Keats' study, another view stretching right across the heath is now obscured by houses.

From where I sit on this bench, I can just see the top of the shard pointing over five miles of buildings. I wonder what this bench looked out at when it was first placed, what significance that view had for the name written next to me? I stood and walked back towards my flat. My suggested route pointed me along the perimeter of the Heath, the thick tangle of trees on my right and a winding road of cars heading into the city on my left. I took another longer route deeper into the trees.

While the views out to the rest of London constantly change, the Heath itself has remained remarkably preserved, so that when you walk deep enough, when the wind blows louder than the traffic, the trees taller than the buildings, it is as though you are walking in the same nature that inspired so many to greatness. You walk among the birds that Keats wrote about, up the hills Charles Pooter took to the pub, the beautiful countryside S. Freud found a year of peace in. And maybe you walk the same quiet lanes that Anna Freud and Dorothy Burlingham took on their way home.

It is a common technique of a museum curator to position furniture, personal items, as though the user has /just/ walked away. In Freud's study, two chairs sit angled away from a table. And though Anna and Dorothy will never walk back to that scene, somewhere new a couple will come home from a love day in London to sit and rest together.